When I have fears that I may cease to be

Before my pen has glean'd my teeming brain,

Before my pen has glean'd my teeming brain,

Before high-piled books, in charactery,

Hold like rich garners the full ripen'd grain;

Hold like rich garners the full ripen'd grain;

When I behold, upon the night's starr'd face,

Huge cloudy symbols of a high romance,

Huge cloudy symbols of a high romance,

And think that I may never live to trace

Their shadows, with the magic hand of chance;

Their shadows, with the magic hand of chance;

And when I feel, fair creature of an hour,

That I shall never look upon thee more,

That I shall never look upon thee more,

Never have relish in the faery power

Of unreflecting love;--then on the shore

Of unreflecting love;--then on the shore

Of the wide world I stand alone, and think

Till love and fame to nothingness do sink.

--John Keats

John Keats (or Key-otts, if a certain someone is still reading this blog) is one of my favorite poets—maybe even my all-time favorite. His writing is extraordinary, and his life was nothing short of romantically tragic. His parents and several siblings died when he was fairly young. Critics wrote scathingly cruel reviews of work. He had a rather unhappy love affair with a certain Fanny Brawne. And Keats himself died at the age of 25 after a horrible and painful battle with tuberculosis.

Keats knew he was dying, and his poetry reflects his hopeless-yet-idealized vision of life. It’s very melodramatic, but I reckon I’d be pretty melodramatic, too, if I were in his shoes.

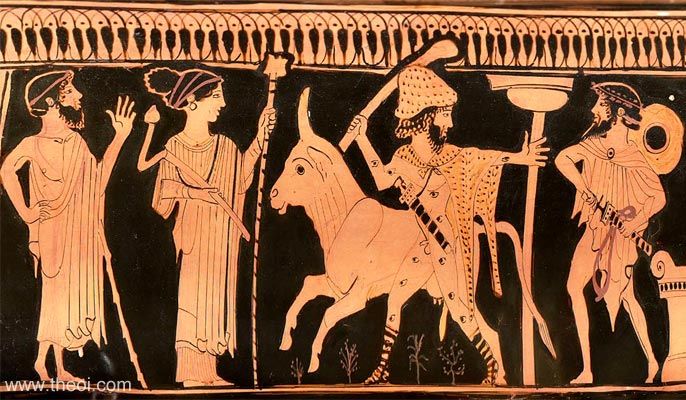

So. I don’t really care to expound upon the poet’s bibliography or greatest works (although please allow me to recommend Ode to a Nightingale, To Sleep, and To Autumn). Instead, I’d like to discuss the curious closing lines of the Ode on a Grecian Urn.

“Beauty is truth, truth beauty”—that is all

Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.

All right. And what exactly does that mean? “Beauty is truth.” So, that which is beautiful is true? What is beauty? I’ve been thinking about the concept of beauty quite a bit lately. (I’d really rather not tackle the definition of “truth” right now. I think I’ll save that for a day when I’m a little braver and a little more motivated.)

I think that, in some ways, we have to be taught an appreciation for the aesthetic. We aren’t born, for example, loving the fine arts. We have to take Humanities classes in order to “get” it. So maybe that sort of beauty (of paintings and pottery) is artificial and also extremely subjective.

Next, there’s a sort of cultural appreciation and definition of beauty. Different groups of people place varying emphases and values on different things. There seems to be a cultural identity and tie that allows people to evaluate what is beautiful.

One thing that almost all peoples seem to have in common, however, is an appreciation for natural beauty. It’s almost as though that’s a sense that’s inborn. Perhaps I’m just naïve, but I personally can’t think of anyone who wouldn’t be awestruck by a truly breathtaking sunset, or who wouldn’t be blown away by a visit to the Garden of the Gods in Colorado (which, I maintain, is the most beautiful place I’ve ever seen).

Then, too, there is a sort of indefinable, transcendental, metaphysical beauty. I can’t express it in words, and I really don’t even have a clue what it is, but it seems to be something that reaches beyond physical senses. This is the beauty of peace and love and the divine.

“The answer must be,” writes Annie Dillard, “that beauty and grace are performed whether or not we will or sense them. The least we can do is try to be there.”

Can we live without beauty? We can exist, certainly, and survive in beauty’s absence. But can we truly live? I don’t know the answer, but I think that part of being a free human being is the ability to love, create, and appreciate beauty in all of its many forms. I think it makes life more enjoyable and valuable.

--John Keats

John Keats (or Key-otts, if a certain someone is still reading this blog) is one of my favorite poets—maybe even my all-time favorite. His writing is extraordinary, and his life was nothing short of romantically tragic. His parents and several siblings died when he was fairly young. Critics wrote scathingly cruel reviews of work. He had a rather unhappy love affair with a certain Fanny Brawne. And Keats himself died at the age of 25 after a horrible and painful battle with tuberculosis.

Keats knew he was dying, and his poetry reflects his hopeless-yet-idealized vision of life. It’s very melodramatic, but I reckon I’d be pretty melodramatic, too, if I were in his shoes.

So. I don’t really care to expound upon the poet’s bibliography or greatest works (although please allow me to recommend Ode to a Nightingale, To Sleep, and To Autumn). Instead, I’d like to discuss the curious closing lines of the Ode on a Grecian Urn.

“Beauty is truth, truth beauty”—that is all

Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.

All right. And what exactly does that mean? “Beauty is truth.” So, that which is beautiful is true? What is beauty? I’ve been thinking about the concept of beauty quite a bit lately. (I’d really rather not tackle the definition of “truth” right now. I think I’ll save that for a day when I’m a little braver and a little more motivated.)

I think that, in some ways, we have to be taught an appreciation for the aesthetic. We aren’t born, for example, loving the fine arts. We have to take Humanities classes in order to “get” it. So maybe that sort of beauty (of paintings and pottery) is artificial and also extremely subjective.

Next, there’s a sort of cultural appreciation and definition of beauty. Different groups of people place varying emphases and values on different things. There seems to be a cultural identity and tie that allows people to evaluate what is beautiful.

One thing that almost all peoples seem to have in common, however, is an appreciation for natural beauty. It’s almost as though that’s a sense that’s inborn. Perhaps I’m just naïve, but I personally can’t think of anyone who wouldn’t be awestruck by a truly breathtaking sunset, or who wouldn’t be blown away by a visit to the Garden of the Gods in Colorado (which, I maintain, is the most beautiful place I’ve ever seen).

Then, too, there is a sort of indefinable, transcendental, metaphysical beauty. I can’t express it in words, and I really don’t even have a clue what it is, but it seems to be something that reaches beyond physical senses. This is the beauty of peace and love and the divine.

“The answer must be,” writes Annie Dillard, “that beauty and grace are performed whether or not we will or sense them. The least we can do is try to be there.”

Can we live without beauty? We can exist, certainly, and survive in beauty’s absence. But can we truly live? I don’t know the answer, but I think that part of being a free human being is the ability to love, create, and appreciate beauty in all of its many forms. I think it makes life more enjoyable and valuable.

2 comments:

This is why we're friends.

I think Dillard's writing is beautiful and romantic and attractive. The idea that we're just smaller parts of something intrinsically valuable, grandiose, lavish, and - dare I say it - divine is so enchanting. It somehow brings me peace to think that I'm small, that the weight of the world is not on me, that we're all part of something bigger together. This was a wonderful post and a great way to start the day. Thank you!

Also, have you ever read Ozymandias by Shelley? Great poem, and this one by Keats reminded me of it for some reason.

My senior English teacher gave us Ozymandias when we were studying Oedipus Rex and the whole concept of hubris, etc. I like that poem. I haven't read a whole lot of Percy Shelley, although I read his wife's Frankenstein over the summer and enjoyed it.

Great stuff!

Post a Comment